Political Trade Unionism: Industrial Cooperation and the Construction of the Class Struggle in Fin de siècle Europe

This book project reconstructs a tradition of thought in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Europe on unions’ role in democratic capitalism. Georges Sorel, Gustave Rouanet, Eugène Fournière, Eduard Bernstein, Jean Jaurès, and Max Weber saw unions as ‘laboratories’ of a new cooperative culture. They were institutions that provided a new framework of education and discipline for the class struggle. Because these figures are not usually considered distinct theorists of unionism, my study of neglected aspects of their thinking provides original insights that demonstrate their place in a common tradition which I call political trade unionism. The project addresses two research questions: how do unions grow their membership and expand a working-class movement? And what transformative functions can they serve in capitalist society?

For these thinkers, unions played a central part in constructing a socialist movement because they created a moral identity among workers in addition to advancing their material interests. In the context of increasing occupational differentiation, workers had diverging material interests. Unions provided workers with a moral education that transcended those issues, enabling them to practice cooperation in production and generating a sense of class belonging. These theorists also believed unions produced working-class leaders who influenced public opinion and passed social legislation in parliament. Given leaders' embeddedness in working-class life, they functioned as journalist-spokesmen and public orators who advocated for legislation that facilitated unionists' collective action. In this tradition, unionist media and oratory mobilized public opinion and secured legislation favorable to economic cooperation.

This project considers this tradition’s implications for labor activism today, notably by exploring lessons for organizing, media infrastructure, and responsible union leadership and protest. It suggests that unions can function as sites of vocational education and independent media that center the value of cooperative production, encouraging a class perspective on questions of employer power. They can train individuals from working-class milieus to become informative, resolutely frank campaigners for working-class interests on the street and within state institutions. These are insights into unionism’s educative and representative functions that can help orient labor activism in the era of digital mass democracy.

Other Works in Progress:

"Gaetano Mosca on the Spirit of Technocracy in Parliamentary Government" contribution to the 'Elite Theory Special Issue' in The European Legacy

"The Conciliar Executive: The Pluralist Case for Semi-Presidentialism in the French Third Republic"

"Corporatism with or without the People? Three Models of Professional Representation in Democracy"

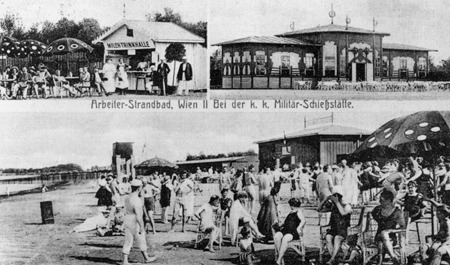

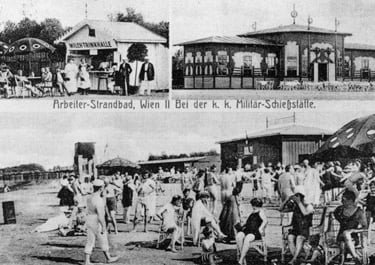

This is a postcard showing the Arbeiterstrandbad or Workers' Bathing Beach in Vienna, Austria, shortly after its opening in 1912. © SPÖ Wien.

This is a photograph of a barricade at a factory in Limoges, France in 1905. © Photothèque Paul Colmar